Post Zang Tumb Tuuum. Art Life Politics: Italia 1918–1943

18 Feb – 25 Jun 2018

Fondazione Prada, Milan

“Post Zang Tumb Tuuum. Art Life Politics: Italia 1918–1943,” conceived and curated by Germano Celant, is an exhibition that explores the world of art and culture in Italy in the interwar years. Based on documentary and photographic evidence of the time, it reconstructs the spatial, temporal, social and political contexts in which the works of art were created and exhibited, and the way in which they were interpreted and received by the public of the time.

The investigation was carried out in partnership with archives, foundations, museums, libraries and private collections and has resulted in the selection of more than 600 paintings, sculptures, drawings, photographs, posters, pieces of furniture, and architectural plans and models created by over 100 authors. In “Post Zang Tumb Tuuum. Art Life Politics: Italia 1918–1943,” these objects are displayed with period images, original publications, letters, magazines, press clippings, and private photographs – for a total of 800 documents – in order to question, as explained by Germano Celant, “the idealism in exhibitions, where works of art, either in museums or other institutions, are displayed in an anonymous, monochromatic environment, generally on a white surface, to connect them to period photographic testimony and reinsert them in their original historical communication space”.

Staged in the Sud gallery, Deposito, Nord Gallery and Podium, the exhibition provides an immersive experience consisting of 24 partial reconstructions of public and private exhibition rooms. These full-size recreations from period photographs contain original works by artists such as Giacomo Balla, Carlo Carrà, Felice Casorati, Giorgio de Chirico, Fortunato Depero, Gerardo Dottori, Filippo de Pisis, Arturo Martini, Fausto Melotti, Giorgio Morandi, Scipione, Gino Severini, Mario Sironi, Arturo Tosi, and Adolfo Wildt, among others.

Consideration of the contemporary social, political and vital context is provided by the exhibition’s presentation of architectural plans, urban planning and large official expositions also conveyed through spectacular projections. Consideration of the social conext of the time is also achieved through thematic focuses dedicated to politicians, intellectuals, writers and thinkers who were active during this period of powerful radicalization of ideas.

At the Fondazione’s Cinema 29 integral newsreels, selected in collaboration with Istituto Luce – Cinecittà, distributed in Italian cinemas between 1929 and 1941. The footage documents the different install and opening phases of some of the most important exhibitions and cultural events of those times.

Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the Universe

Guggenheim, New YorkThe Guggenheim’s new survey of Italian futurism speeds up the museum’s spiral ramp, popping with invention and bursts of rhetoric. But the show slows as it rises, until it pants and plods into the movement’s dotage on the upper floors. Futurism had a pair of explosive stars whose ends, nearly 30 years apart, defined its first and second acts. In his paintings and sculptures, Umberto Boccioni dismantled old pieties and rebuilt awkwardness into dynamic elegance. He was killed in 1916, and if the exhibition had ended there it would have told only the story’s glorious beginning. Instead, the show perseveres until the death in 1944 of futurism’s three-named, sartorially splendid, relentlessly provocative and prodigiously mustachioed propagandist, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Almost immediately, we come face to mangled face with “Antigraceful”, Boccioni’s brilliantly unsentimental 1913 portrait of his mother and muse. He spared her no violence, gouging her round, comfortable features into grotesque clods. She has been ravaged by the forces of modernity, flayed into strands of the cityscape all around. Boccioni collapses space and time into bronze, making his mother’s image the portrait of an age. “We must smash, demolish and destroy our traditional harmony, which makes us fall into a gracefulness created by timid and sentimental cubs,” he proclaimed. He loved his mother and painted her often, but he was no timorous pup. He paid her the honour of plucking her from filial corniness. Boccioni both embodied and transcended futurism’s speed-drunk bombast. In “Dynamism of a Cyclist”, gold, green, fuchsia, and indigo shards collide and rearrange themselves into a portrait of pure, hectic energy. “The City Rises” goes further, weaving horses, motorcars, factories and pavement into a kaleidoscopic tapestry of feverish rhythms. Here and in the monumental triptych “States of Mind” Boccioni merged physical and psychological reality. He captured the way it feels to be tossed in the tumult of a train station, and analysed the way we project emotions on to our surroundings. The oblique tilt of “Those Who Go” conveys the “loneliness, anguish and dazed confusion” of departure. In “Those Who Stay”, staid verticality hints at the static sadness of loved ones left behind. Boccioni craved war and died young. He volunteered for the Italian army, and was hurled from his saddle during a training exercise. It’s hard not to speculate about his thoughts during his final seconds: he might have preferred to be thrown from an irreproachably modern car instead of an antediluvian horse, but perhaps he savoured the experience of lethal momentum. In any case, his quick death was the beginning of the movement’s protracted end. Curator Vivien Greene does a superlative job of tracing the movement’s birth and trajectory, and she is determined to see it through to the spluttering finale. To the roster of well-known names – Marinetti, Boccioni, Carra, Balla, Severini, Sant’Elia – she adds another cohort, responsible for the muted, mechanistic and deadened iterations of the 1920s and 30s. They include Fortunato Depero, who dabbled in posters, puppetry and graphic design, visited New York in 1928 and produced a series of inert city views. The point of Greene’s thoroughness is not to trumpet mediocrity but to examine the movement in all its moral and political complexity. Futurism, like fascism, was an attitude more than a philosophy, a glorification of youth, action and militarism concentrated in a leader’s personality. That artistic Caesar was Marinetti, who in turn fawned on Mussolini – at least until the Duce declined to anoint futurism as the state’s official art. Born in Egypt to Italian parents and educated in France, Marinetti was both a cosmopolitan and a zealous nationalist, hamming it up on an international stage. The manifesto he penned in 1909 – by far his most brilliant achievement – appeared on the front page of Le Figaro, France’s leading daily. The magniloquent Marinetti wrote like Whitman on speed, exalting “movements of aggression, feverish sleeplessness, the double march, the perilous leap, the slap and the blow with the fist”. He extolled the dynamism of urban life, the rat-tat-tat of industry and the vibrancy of transit. “A roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace,” he declared. To Marinetti, modernity meant violence, which he thought of as a cleansing force, wiping away obsolete sentimentalism in spasms of masculine energy. “We want to glorify war – the only cure for the world – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman.” That last clause seems to have embarrassed the Guggenheim, which puts it out there with little comment or context. In his manifesto, Marinetti placed feminism alongside museums and libraries as aspects of an exhausted culture to be wiped away. That position only sort of aligned with fascist orthodoxy, which treated women as precious machines for popping out babies and increasing the ranks of patriots. Rather than lingering on the movement’s revulsion towards the less swashbuckling sex, Greene includes a few decorative but not distinctive works by Benedetta Cappa, who was virtually the movement’s sole female painter – and Marinetti’s long-suffering wife. In her pursuit of comprehensiveness, Greene toughs out the dullness and disappointment of the final chapter. She can’t prevent the show from fizzling in synch with its subject, but she does lay out a nuanced understanding of why the futurists failed. For most of the 1920s and 30s, they tried to reconcile their desire for freshness with their militarism, to marry their programme of perpetual upheaval to the increasingly conservative tastes of the regime. The paradox was bound to fall apart. Inevitably, an iconography of flux ossified into a catalogue of bellicose emblems: aircraft, tanks and radio towers. Already by its second decade, Futurism was trapped in a credo of newness that proved unable to adapt.

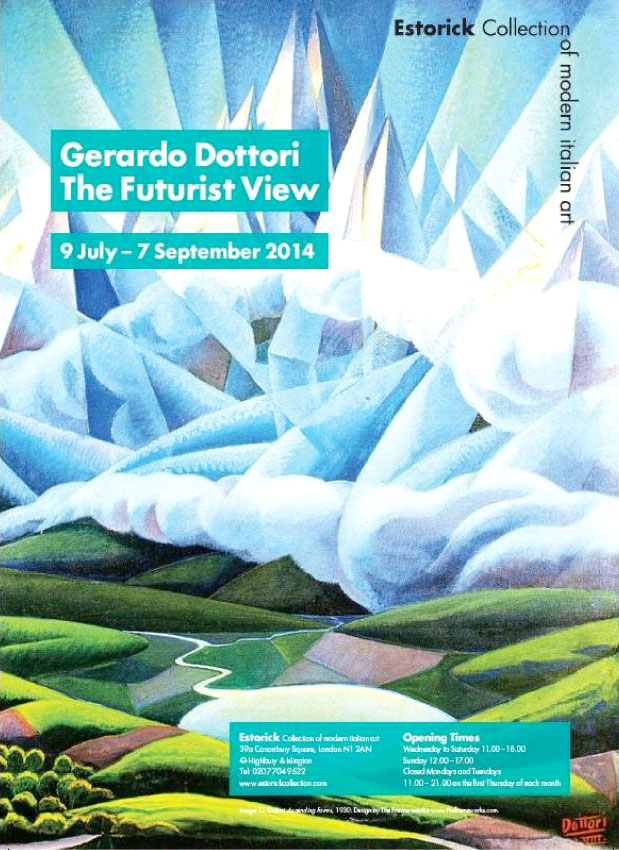

Gerardo Dottori the Futurist View

Estorick Collection, LondonGerardo Dottori (1884-1977) was one of the pivotal figures of Italian Futurism during the inter-war years. His expansive and intensely poetic visions of the Umbrian landscape, viewed from above, were among the earliest and most striking examples of ‘aeropainting’ – the dominant trend within Futurist art throughout the 1930s, exploring the dynamic perspectives offered by flight.

Dottori was born in Perugia and studied at the city’s Accademia di Belle Arti, where he revealed himself to be a superbly accomplished draughtsman. Around 1904 he began to experiment with Divisionism (Italy’s distinctive response to Neo-Impressionism) which introduced a newfound sense of spontaneity and exuberance into his art, liberating him from the restrictions of his academic training. Dottori’s rebellious temperament made him naturally receptive to the subversive spirit of F. T. Marinetti’s Futurist movement, which he joined in 1912.

Futurism is most closely associated with its celebration of the flux and dynamism of the modern industrial age – which permeates Dottori’s imagery. However he also remained deeply attached to his native region of Umbria and its lush, undulating landscape, frequently expressing his preference for ‘the stillness of the countryside and the mountains to the deafening noise of big cities’. Whilst this might seem a paradoxical stance for a Futurist to adopt, the movement in fact offered artists significant latitude in their interpretation of its ideas, prizing innovation and creative vitality above all else. Consequently, Dottori was able to express his Futurist sensibility through imagery exploring that ‘universal’ dynamism apparent in the workings of nature, the human body and the cosmos, as well as that generated by machinery.

Dottori’s greatest contribution to Futurist aesthetics was his distinctive interpretation of aeropainting. In fact, a number of his works of the 1920s can be said to have anticipated the genre’s concerns, encapsulated in the belief that ‘the changing perspectives of flight constitute an absolutely new reality, one that has nothing in common with the reality traditionally constituted by earthbound perspectives’. With their sweeping panoramas and distorted horizons, suggesting the curvature of the earth, Dottori’s aeropaintings are infused with an atmosphere of serenity and lyricism that is unique in Futurist art.

Drawing on works from a number of public and private collections, The Futurist View provides an authoritative survey of the career of one of Futurism’s most significant and distinctive artists.